What's The Future For Distributed Energy In Texas?

Most news articles on the recent ERCOT proposal regarding distributed energy production are full of jargon and technobabble, and not incredibly easy to understand. And that’s a shame given a policy proposal that could very well revolutionize the relationship between Texas consumers and the energy they consume.

So we break it down for you here.

Introduction

Despite its enormous solar potential, so far Texas has lagged behind other states like New York and California when it comes to residential adoption of solar, through companies like SolarCity. This is largely because Texas has lacked “net metering,” which essentially allows your electric meter to run backwards—subtracting the excess energy that you produce and send out to the grid from the energy that you consume.

Because of an inability to store energy for consumption later, residential solar producers still need to purchase electricity during the times of day when their demand exceeds what their rooftop solar panels are producing. As such, this process of net metering is what makes residential solar economically viable for most customers, giving them an incentive to install panels by allowing them to save, or even make money, every month.

Recently, ERCOT, the organization that manages Texas’s liberalized energy grid, has moved to address this problem. ERCOT’s proposal is somewhat different than the net-metering that happens in other states, and centers around three different categories of “distributed energy resources,” (or DER) like residential solar. These are “DER Minimal,” “DER Light,” and “DER Heavy.”

But before going there, let’s back up a bit and run through how ERCOT functions today.

How the Market Works Today

ERCOT, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, is a wholesale energy market that serves 23 million people and distributes about 90% of the electricity used in Texas. As a liberalized market, ERCOT is a place where electricity is bought and sold between power producers and electricity retail companies, and then transmitted to individual consumers.

Electricity markets are unique, in that they provide an immediate good. When you shop around for a computer, you can delay your purchase to read reviews, test out different products, and finally order one. And if the one you want is sold out and you have to wait a day or two for it to arrive, well that might be annoying, but you can totally deal with it. Electricity, on the other hand, is an immediate good. When you flick the light switch on, it needs to be there with no delay.

So electricity grids have a big coordination problem—at some points during the day, demand is far higher than at other points. And this doesn’t necessarily correspond to when the cheapest (or greenest) forms of energy are being produced. As such, ERCOT needs to do some forecasting of demand, and power producers need to have extra capacity that they can bring online when demand begins to rise.

All of this requires lots of connection and communication between ERCOT, utility companies, and power production plants. Because as a liberalized market, this response happens based on price, ERCOT requires even more connections in order to increase efficiency, and allow greater differentiation in price between producers and the geographic areas of highest demand for electricity. But historically, ERCOT functioned as just four different zones, each with its own average price for electricity.

To respond to that, and increase the functionality of its market, in 2006 ERCOT began implementing its “nodal” project.

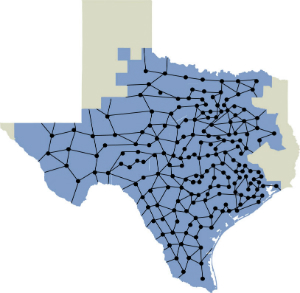

ERCOT's major node connection points

Net Metering and the Nodes

Singers hear the word “nodes” and become immediately terrified of the vocal chord bumps that can develop and impact their ability to sing. ERCOT’s nodes have nothing to do with that.

Instead, the nodes are 8,200 connection points that are able to offer different price information every five minutes. This allows for more refined competition among producers and more choice for wholesale electricity buyers, but why does it necessarily matter for distributed energy production?

Because here’s how net metering works, a little more in-depth this time. Imagine that there are solar panels on your roof. They are great at producing energy at certain times of the day, but at other times, less so. (Exactly what times can depend on their orientation. South facing panels are the most common, because they produce the most overall energy year-round, though production tends to be concentrated around midday, whereas west-facing panels are better at generating power in the late afternoon).

And so those solar panels on your roof might be producing most of their energy at a time of day when your consumption is lowest, because you are off at work, or whatever. If only you can consume the energy you generate, then this is a big waste of electricity, but also of money. But if you could send the power back out into the grid, say to be consumed by your neighbors (ideally, because less would be lost due to transmitting energy over a distance), and be compensated for it, then more renewable energy would be consumed, and you would have a monetary incentive for installing those solar panels.

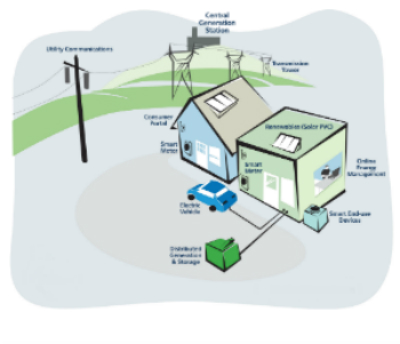

Enter net metering. Smart meters and grids enabled for this allow electricity flow to be tracked both ways—electricity that flows in to your home from the grid is tracked and billed like normal, and when you produce excess electricity, it is sent back out to the grid, causing your meter to run backwards, subtracting your production from your consumption. And if this production is great enough, instead of paying an electric bill, your utility could be paying you.

Traditional net metering operates under guaranteed payment; the electricity you produce and sell into the grid is guaranteed the same retail price as other consumers pay for their power. But because of its nodal system, ERCOT envisions this working somewhat differently.

ERCOT's Proposals

ERCOT is planning three different categories of registration for its distributed energy resources (DER). Minimal, Light, and Heavy. Let’s take a closer look at the differences, and what each one means.

DER Minimal

This first category is more or less “business as usual.” DER Minimal areas are load zones in the West, North, and South of the state, as well as the Houston area. DER Minimal:

- Lacks a mechanism to link DER payments to nodal pricing

- Will be aggregated and treated as single units

- Will receive average wholesale electricity price in each of the four zones

So in other words, all of the solar panels on rooftops on your block would be treated as one single energy production site in order for tracking and pricing to work.

DER Light

ERCOT hopes to shift a lot of DER Minimal to DER Light, which would allow for some big improvements over the existing system. In these areas, resources would:

- continue to be aggregated

- “two way distributed participation”—in plain English, storage, like the Tesla Powerwall or other home battery systems—would be taken into account as well.

- be priced at a nodal level

This is an important step in creating the groundwork for future “smart” electric grids with advanced abilities to engage in demand response, and store energy at peak renewable production to be accessed later when demand increases. Additionally, pricing at a nodal level would increase the incentives to install solar and other distributed energy production in the places with the highest energy prices, and so increase the overall efficiency of the grid and the market.

DER Heavy

The last category is more commercially than residentially oriented. It would allow for:

- even better geographic pricing

- DERs to participate fully in energy and ancillary markets.

Ie, they would be able to engage with utilities' demand response programs in order to react quickly to changes in supply and demand on the grid, and access more lucrative payments. Being able to do this requires the same sort of real time communication and metering links that exist at big power plants, and so most residential customers would not be concerned with this level of participation.